Wombat tasmański

| Vombatus ursinus | |||||

| (G. Shaw, 1800)[1] | |||||

| |||||

| Systematyka | |||||

| Domena | eukarionty | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Królestwo | zwierzęta | ||||

| Typ | strunowce | ||||

| Gromada | ssaki | ||||

| Nadrząd | torbacze | ||||

| Rząd | dwuprzodozębowce | ||||

| Rodzina | wombatowate | ||||

| Rodzaj | wombat | ||||

| Gatunek | wombat tasmański | ||||

| |||||

| Podgatunki | |||||

| | |||||

| Kategoria zagrożenia (CKGZ)[20] | |||||

| |||||

| Zasięg występowania | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

Wombat tasmański[21][22] (Vombatus ursinus) – średniej wielkości gatunek ssaka z rodziny wombatowatych (Vombatidae) przypominający wyglądem borsuka, o jednolitej, szarej sierści. Występuje na obszarze Australii od granic Queensland i Nowej Południowej Walii wzdłuż pustyń Wiktorii aż do południowo-wschodniego krańca Australii oraz na Tasmanii.

Taksonomia

Gatunek po raz pierwszy zgodnie z zasadami nazewnictwa binominalnego opisał w 1800 roku brytyjski zoolog i botanik George Shaw nadając mu nazwę Didelphis ursina[1]. Miejsce typowe w oryginalnym opisie to „Nowa Holondia”, tj. Australia[23][24][25].

Jest jedynym żyjącym współcześnie przedstawicielem rodzaju wombat (Vombatus)[26][23][27][24][25].

Autorzy Illustrated Checklist of the Mammals of the World rozpoznają trzy podgatunki[23]. Podstawowe dane taksonomiczne podgatunków (oprócz nominatywnego) przedstawia poniższa tabelka:

| Podgatunek | Oryginalna nazwa | Autor i rok opisu | Miejsce typowe |

|---|---|---|---|

| V. u. hirsutus | Opossum hirsutum | Perry, 1810 | Botany Bay, Sydney, Australia[28]. |

| V. u. tasmaniensis | Vombatus ursinus tasmaniensis | W.B. Spencer & Kershaw, 1910 | Tasmania, Australia[18][28]. |

Etymologia

- Vombatus: ang. wombat ‘wombat’, zniekształcenie od rodzimych, aborygeńskich nazw womback lub wombach dla wombata[29].

- ursinus: łac. ursinus ‘niedźwiedziowaty, jak niedźwiedź’, od ursus ‘niedźwiedź’; przyrostek -inus ‘odnoszący się do, jak’[30].

- hirsutus: łac. hirsutus ‘włochaty’, od hirtus ‘włosy’[31].

- tasmaniensis: Tasmania, Australia[18].

Zasięg występowania

Wombat tasmański występuje w zależności od podgatunku[25]:

- V. ursinus ursinus – Cieśnina Bassa (Wyspa Flindersa)

- V. ursinus hirsutus – kontynentalna południowo-wschodnia Australia

- V. ursinus tasmaniensis – Tasmania

Morfologia

Długość ciała 90–115 cm; masa ciała 22–40 kg[25][27].

Dane liczbowe

- dojrzałość płciowa: 2 lata

- ciąża: 20-22 dni

- liczba młodych: 1

- długość życia: do 20 lat

Występowanie i środowisko

Pagórkowate tereny pustynne i wzdłuż lasów. Mieszkają w norach, które służą również jako kryjówka w przypadku niebezpieczeństwa. Jeden wombat może posiadać nawet 10 nor. Wombat wygrzebuje nory przednimi łapami zaopatrzonymi w długie i ostre pazury. W pobliżu wejścia do nory często wygrzebuje płytki dołek, w którym wygrzewa się w porannym słońcu. Aktywny głównie nocą.

Odżywianie

Wombaty żywią się głównie trawami, jadają również owoce, korzonki, korę oraz liście drzew i krzewów. Wombat gryzie pożywienie za pomocą szybkich ruchów szczęki dolnej, jego zęby różnią się od innych torbaczy, przypominają zęby gryzoni. Przez całe życie zęby zwierzęcia nieustannie rosną, gdyż są na bieżąco ścierane.

Rozmnażanie

Pora godowa trwa od kwietnia do czerwca i jest to jedyny okres kiedy wombaty rezygnują z samotnego życia. Po około 20 dniach ciąży samica rodzi jedno młode w fazie embrionalnej (około 22 mm długości i waga ok. 2 gramów). Dzięki wczesnemu wykształceniu się dobrze rozwiniętych, przednich łap, młode dociera do torby lęgowej otwierającej się ku tyłowi, inaczej niż u innych torbaczy. Dzięki temu, do wnętrza torby nie dostaje się ziemia i piach podczas kopania nory lub szukania pożywienia przez matkę. Przez kolejne sześć miesięcy młode przysysa się do jednego z sutków, który obficie zaopatruje je w odżywcze mleko.

Status zagrożenia i ochrona

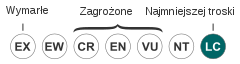

Gatunek nie jest zagrożony wyginięciem, poza regionem Wiktorii. Mimo to postanowiono ograniczyć polowania. W Czerwonej księdze gatunków zagrożonych Międzynarodowej Unii Ochrony Przyrody i Jej Zasobów został zaliczony do kategorii LC (ang. least concern „najmniejszej troski”)[20].

Zobacz też

Uwagi

Przypisy

- ↑ a b c d G. Shaw: General zoology, or Systematic natural history. T. 1. Cz. 2: Mammalia. London: G. Kearsley, 1800, s. 504. (ang.).

- ↑ C. Bertuch. Nachricht von einigen neuen zoologischen Endtekungen. „Magazin für den neuesten Zustand der Naturkunde”. 4 (5), s. 691, 1802. (niem.).

- ↑ A.G. Desmarest: Nouveau dictionnaire d’histoire naturelle appliquée aux arts: principalement à l’agriculture et à l’économie rurale et domestique: par une societe de naturalistes et d’agricultueurs: avec figures tirees des trois regnes de la nature. T. 24. Paris: Chez Deterville, 1804, s. 20. (fr.).

- ↑ Ch.A. Lesueur & S.L. Petit: Atlas. W: F.A. Péron & C.A. Lesueur: Voyage de découvertes aux terres australes: exécuté par ordre de Sa Majesté l’empereur et roi, sur les corvettes le Géographe, le Naturaliste, et la goëlette le Casuarina, pendent les années 1800, 1801, 1802, 1803 et 1804. Cz. 1. Paris: De l'Imprimerie impériale, 1807, s. ryc. xxviii. (fr.).

- ↑ F. Tiedemann: Zoologie: zu seinen Vorlesungen entworfen. Allgemeine Zoologie, Mensch und Säugthiere. Landshut: In der Weberichen Buchhandlung, 1808, s. 437. (niem.).

- ↑ a b G. Perry: Arcana, or, The museum of natural history: containing the most recent discovered objects: embellished with coloured plates, and corresponding descriptions: with extracts relating to animals, and remarks of celebrated travellers; combining a general survey of nature. London: Printed by George Smeeton for James Stratford, 1811, s. sygn. M1. (ang.).

- ↑ W.E. Leach: The zoological miscellany, or being descriptions of new, or interesting animals. Cz. 2. London: Printed by B. McMillan for E. Nodder & Son and sold by all booksellers, 1815, s. 102. (ang.).

- ↑ R.-P. Lesson: Manuel de mammalogie, ou histoire naturelle des mammiferes. Paris: J. B. Bailliere, 1827, s. 229. (ang.).

- ↑ R. Owen: Phascolomys Mitchellii. W: T.L. Mitchell: Three expeditions into the interior of eastern Australia; with descriptions of the recently explored region of Australia Felix, and of the present colony of New South Wales. Cz. 2. London: T. and W. Boone, 1839, s. 368. (ang.).

- ↑ R. Owen: Descriptive catalogue of the osteological series contained in the museum of the royal college of surgeons of England. Cz. 1. London: Taylor and Francis, 1853, s. 334. (ang.).

- ↑ J. Gould: The mammals of Australia. Cz. 1. London: Printed by Taylor and Francis, pub. by the author, 1863, s. ryc. lx i tekst. (ang.).

- ↑ Gray 1863 ↓, s. 458.

- ↑ Gray 1863 ↓, s. 459.

- ↑ J.L.G. Krefft. Letter from, on the Species of Wombat (Phascolomys). „Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London”. For the year 1872, s. 796, 1872. (ang.).

- ↑ Owen 1872 ↓, s. 192.

- ↑ Owen 1872 ↓, s. 193.

- ↑ F. McCoy: Prodromus of the palaeontology of Victoria: or, Figures and descriptions of Victorian organic remains. Cz. 1. Melbourne: G. Skinner, acting government printer, 1874, s. 21. (ang.).

- ↑ a b c B. Spencer & J.A. Kershaw. On the existing species of the genus Phascolomys. „Memoirs of the National Museum, Melbourne”. 3, s. 58, 1910. (ang.).

- ↑ S.M. Jackson, J.J. Jansen, G. Baglione & C. Callou. Mammals collected and illustrated by the Baudin Expedition to Australia and Timor (1800-1804): A review of the current taxonomy of specimens in the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle de Paris and the illustrations in the Muséum d’Histoire naturelle du Havre. „Zoosystema”. 43 (21), s. 405, 2021. DOI: 10.5252/zoosystema2021v43a21. (ang.).

- ↑ a b Vombatus ursinus, [w:] The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (ang.).

- ↑ W. Cichocki, A. Ważna, J. Cichocki, E. Rajska-Jurgiel, A. Jasiński & W. Bogdanowicz: Polskie nazewnictwo ssaków świata. Warszawa: Muzeum i Instytut Zoologii PAN, 2015, s. 10. ISBN 978-83-88147-15-9. (pol. • ang.).

- ↑ Z. Kraczkiewicz: SSAKI. Wrocław: Polskie Towarzystwo Zoologiczne – Komisja Nazewnictwa Zwierząt Kręgowych, 1968, s. 81, seria: Polskie nazewnictwo zoologiczne.

- ↑ a b c C.J. Burgin, D.E. Wilson, R.A. Mittermeier, A.B. Rylands, T.E. Lacher & W. Sechrest: Illustrated Checklist of the Mammals of the World. Cz. 1: Monotremata to Rodentia. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, 2020, s. 74. ISBN 978-84-16728-34-3. (ang.).

- ↑ a b N. Upham, C. Burgin, J. Widness, M. Becker, C. Parker, S. Liphardt, I. Rochon & D. Huckaby: Vombatus ursinus (G. Shaw, 1800). [w:] ASM Mammal Diversity Database (Version 1.11) [on-line]. American Society of Mammalogists. [dostęp 2023-08-01]. (ang.).

- ↑ a b c d R. Wells: Family Vombatidae (Wombats). W: D.E. Wilson & R.A. Mittermeier (redaktorzy): Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Cz. 5: Monotremes and Marsupials. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, 2015, s. 433–434. ISBN 978-84-96553-99-6. (ang.).

- ↑ D.E. Wilson & D.M. Reeder (redaktorzy): Species Vombatus ursinus. [w:] Mammal Species of the World. A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (Wyd. 3) [on-line]. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. [dostęp 2020-08-07].

- ↑ a b Class Mammalia. W: Lynx Nature Books (A. Monadjem (przedmowa) & C.J. Burgin (wstęp)): All the Mammals of the World. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, 2023, s. 52. ISBN 978-84-16728-66-4. (ang.).

- ↑ a b S.M. Jackson & C.P. Groves: Taxonomy of Australian Mammals. Clayton South: CSIRO Publishing, 2015, s. 101. ISBN 978-1-486-30012-9. (ang.).

- ↑ T.S. Palmer. Index Generum Mammalium: a List of the Genera and Families of Mammals. „North American Fauna”. 23, s. 708, 1904. (ang.).

- ↑ Edmund C.E.C. Jaeger Edmund C.E.C., Source-book of biological names and terms, wyd. 1, Springfield: Charles C. Thomas, 1944, s. 247, OCLC 637083062 (ang.).

- ↑ hirsutus, [w:] The Key to Scientific Names, J.A.J.A. Jobling (red.), [w:] Birds of the World, S.M. Billerman et al. (red.), Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca [dostęp 2023-08-01] (ang.).

Bibliografia

- J.E. Gray. Notice of three wombats in the Zoological Gardens. „The Annals and Magazine of Natural History”. Third series. 11 (66), s. 457–459, 1863. (ang.).

- R. Owen. On the Fossil Mammals of Australia . — Part VI. Genus Phascolomys, Geoffr. „Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London”. 162 (1), s. 173–196, 1872. (ang.).

- Mały słownik zoologiczny: ssaki. Warszawa: Wiedza Powszechna, 1978.

- Encyklopedia zwierząt od A do Z. ISBN 83-908277-3-5.

- Watson, A.: Vombatus ursinus. (On-line), Animal Diversity Web, 1999. [dostęp 2008-12-21]. (ang.).

- J9U: 987007551700805171

- Britannica: animal/common-wombat